A magazine where the digital world meets the real world.

On the web

- Home

- Browse by date

- Browse by topic

- Enter the maze

- Follow our blog

- Follow us on Twitter

- Resources for teachers

- Subscribe

In print

What is cs4fn?

- About us

- Contact us

- Partners

- Privacy and cookies

- Copyright and contributions

- Links to other fun sites

- Complete our questionnaire, give us feedback

Search:

Back (page) to reality

We have been discussing Illusions and reality a lot in recent articles, so given how important language is to Computer Science, it's only right to include some word tricks. Understanding how we turn the written word into understanding is a real challenge for computer scientists. Get it right and you can build computers that understand the written word, a really useful thing to do. First off when we look at a written sentence there are two parts to it, the syntax and the semantics.

A word spell

Syntax is about the structure of language - what is allowed to follow what, ignoring what it means. Turns out the order of letters matters very little to humans. How do we read words? Do we pay attention to every single letter to be able to extract the information? Perhaps not! Perhaps we recognise words and give them meaning with a lot less information. Try and read the paragraph below.

'Aoccdrnig to rscheearch, it deosn't mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrod are, the olny iprmoetnt tihng is taht the frist and lsat ltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a toatl mses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihs is bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteter by istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe'

We humans can get the gist of it even though the data is very messy, but imagine how a poor computer would do, trying to match each letter to a set of stored words. The typos would floor it! So that's why examining how humans read and understand is an important area of research.

The trick is: Perfect the start and finish

It's not what you say it's the way that you say it

Semantics is trickier. It's about the meaning of words. Put the stress when you speak a sentence in a different place and you can change the reality!

'I didn't steal granny's chocolate cake '- Wasn't me, was someone else!

'I didn't steal granny's chocolate cake '- It really wasn't me!

'I didn't steal granny's chocolate cake '- I planed to give it back, honest!

'I didn't steal granny's chocolate cake '- It was actually Uncle Johns I stole!

'I didn't steal granny's chocolate cake '- It was her vanilla sponge cake I nicked!

'I didn't steal granny's chocolate cake ' - It was her bar of chocolate!

How does a computer work that out from the words alone!

The trick is: say it like you mean it

The computer is better than you! (well sometimes)

Quickly count the number of letter 'F''s in the following:

FINISHED FILES ARE THE RESULT OF YEARS OF SCIENTIFIC STUDY COMBINED WITH THE EXPERIENCE OF YEARS

How many did you get? 3 or 4? In fact there are 6 F's. During a quick read, your eyes and brain fix on the meaningful (lexical) words, and tend to ignore the grammatical syntactic words (like the three 'of's). Young children aged 6 tend not to make this mistake. They take each word in turn slowly so can count the number of 'F's correctly, as would a current computer program. When you get older your brain starts to learn to take shortcuts in reading to make it more fluid.

The trick is: fast and fluid usually gets you there

Colouring your perception

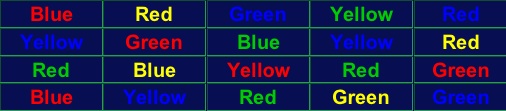

Say the colour of the following words out loud quickly

Easy ...?

I bet you read the word rather than the colour! This is a really powerful illusion called the Stroop effect, named after its discoverer John Ridley Stroop in 1935. He found that if you have to say colours quickly then Green written in green will normally cause less of an error than Green written in blue, as the word and it's colour are conflicting information that your brain can't cope with. It shows again that your brain uses shortcuts to deal with all the information you're throwing at it. It makes assumptions and when those assumptions are wrong, your brain makes a mistake and an illusion happens.

The trick is: don't trust your brain

Studying how the brain makes mistakes give us a valuable insight into how it works, and since most of the time it does a really good job of things, building computers that follow the same processes, even if they suffer the same illusions, is a very useful thing to do.

You can trust your brain most of the time, but when its assumptions are wrong, illusions follow...

More on ...

Psychophysics: Say have you heard about the one about the McGurk effect? IllusionsBack to...

Magazine+: Special Issue on IllusionsCompetitions

Current CompetitionsThe Maze

Up on a balcony a group of poets take turns to invent the next line of a limerick.

On a wall is a painting that gives the illusion of being a yellow brick road.