A magazine where the digital world meets the real world.

On the web

- Home

- Browse by date

- Browse by topic

- Enter the maze

- Follow our blog

- Follow us on Twitter

- Resources for teachers

- Subscribe

In print

What is cs4fn?

- About us

- Contact us

- Partners

- Privacy and cookies

- Copyright and contributions

- Links to other fun sites

- Complete our questionnaire, give us feedback

Search:

Beatboxing with a very different voice

At first it sounds like a primitive PlayStation making babytalk. There’s a jumble of electronic bleeps and fuzzes coming out of the speakers, but with a kind of human sound too, like gargling and cooing. Soon the strange noises take on a rhythm, and it’s like a combination of a drum machine, someone’s voice and the soundtrack from the original Super Mario Bros. That may be hard to imagine, but there’s a good reason. When Dan Stowell a PhD student at Queen Mary, beatboxes, it’s a sound you’ve never really heard before.

In regular beatboxing, performers try and fake the sounds of drumbeats, synthesisers and DJ-ing using only their voice and a microphone. Dan’s been beatboxing for about seven years, but the extra weird sounds in his performance are from something new: he’s found a way to hook the sound card from a retro computer up to his microphone. His voice gets translated through the system so whatever sound he makes, from a clunk to a hiss to a chk-chk-chk, it comes out in the voice of the biggest home computing star of 1985, the ZX Spectrum.

Express yourself

Why do this? Because every day we humans use one of the most expressive instruments on the planet – our voice. Dan wants to capture that expressiveness and use it to control musical instruments too. “If I want to make music,” he says, “surely I should just be able to go ‘it goes like this – blah blah brah rah rah’ rather than having to learn how to play a MIDI keyboard or anything like that.”

If you’ve ever taken music lessons, you’ll know that you spend most of the time in the beginning just learning how to get the notes right. You have to know your own instrument pretty well before you can start adding expressiveness and mood into the mix. Part of the reason for that is that there aren’t many ways to change the sounds you make. Dan uses a keyboard as an example. Even on an expensive keyboard you can only really change the notes you play, how fast you play them, and how loudly. “So if you want to make sad music you have to know how to do it on that specific instrument. But everyone knows how to make mood with their voice – we do it every day. And a voice can communicate so much all at once. There’s lots of information.”

Maths and maps

The actual business of turning Dan’s beatboxing into computerised bleeps depends, in part, on some good maths. For every moment of his performance, a computer analyses the sound of his voice. “You just get a load of numbers out,” says Dan. A sound wave contains lots of information, so when he was designing the system, one of the toughest bits was deciding which information to keep and use. What’s more, the sort of information Dan really wanted is the kind of stuff that humans can pick out of a sound pretty easily, but computers find difficult. “Is it growly, is it whispery, is it strained? Is it sad, is it happy? Those sorts of things are still really quite slippery.”

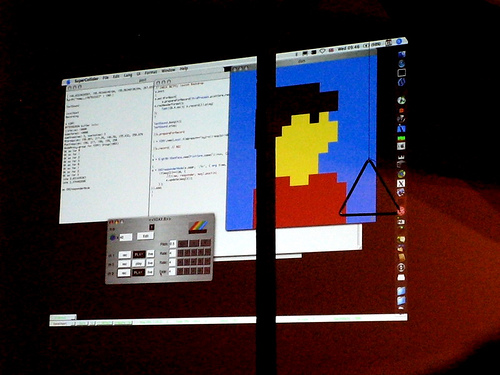

What he had to do was shave off lots of the numbers until he was left with only the best ways of measuring all those hard-to-define qualities of a sound. While he’s beatboxing, the computer tracks and measures just those qualities and spits out numbers for them. That still leaves the problem of translating those numbers into ZX Spectrum noises. And to solve it, Dan made a map.

Dan’s map was of the different sounds the Spectrum sound card could make. A really loud, hissy noise would be at one side, for example, and a really soft, pure tone would be at the opposite end. You can divide up any map into precise spaces by giving them co-ordinates – numbers that tell you what position you’re in. So once he’d made the map of Spectrum sounds, he gave them all numbers that would correspond to the ones his computer sends out during his performance, while it’s tracking his voice. As Dan explains, it’s “just like you might take two printed maps and put them one on top of the other and say, ‘if I’m here in my voice map I should be here in the synthesiser map’.” So if Dan makes a really hissy sound with his voice, the computer looks up the equivalent hissy sound on the ZX Spectrum sound map and plays it. What’s more, because no one ever programmed the Spectrum to make such strange, voice-like noises back in its ‘80s heyday, Dan says “pretty much everything I do is a sound that the ZX Spectrum never made”.

Follow the sound of my voice

Dan will eventually get a PhD from Queen Mary out of all this work, since teaching computers to analyse the human voice is something new in electronics research. Even so, his beatbox synthesiser has always been something he wants to use in real world performances. And he wants to get to the point where it’s not just one synth he’s controlling. He’s looking forward to performing with a whole bank of synthesisers, all tuned to the sound of his voice. One day you might even be able to play an instrument without really knowing how – all you’d have to do is sing a line and it would come out of the speakers sounding like a keyboard, a cello or whatever instrument you wanted. Which means that in the future, any good singer (or beatboxer) could have a whole band (or even an orchestra) at their disposal.

Top image courtesy of Dan Stowell. Bottom image courtesy of Rain Rabbit.