A magazine where the digital world meets the real world.

On the web

- Home

- Browse by date

- Browse by topic

- Enter the maze

- Follow our blog

- Follow us on Twitter

- Resources for teachers

- Subscribe

In print

What is cs4fn?

- About us

- Contact us

- Partners

- Privacy and cookies

- Copyright and contributions

- Links to other fun sites

- Complete our questionnaire, give us feedback

Search:

Gadgets based on works of fiction

by Paul Curzon, Queen Mary University of London

Why might a computer scientist need to write fiction? To make sure she creates an app that people actually need.

Writing fiction doesn't sound like the sort of skill a computer scientist might need. However, it's part of my job at the moment. Working with expert rheumatologists Amy MacBrayne and Fran Humby, I am helping a design team understand what life with rheumatoid arthritis is like, so they can design software that is actually needed and so will be used and useful.

A big problem with developing software is that programmers tend to design things for themselves. However, programmers are not like the users of their software. They have different backgrounds and needs and they have been trained to think differently. Worse, they know the system they are developing inside out, unlike its users. An important first step in a project is to do background research to understand your users. If designing an app for people with rheumatoid arthritis, you need to know a lot about the lives of such people. To design a successful product, you particularly need to understand their unfulfilled goals. What do they want to be able to do that is currently hard or impossible?

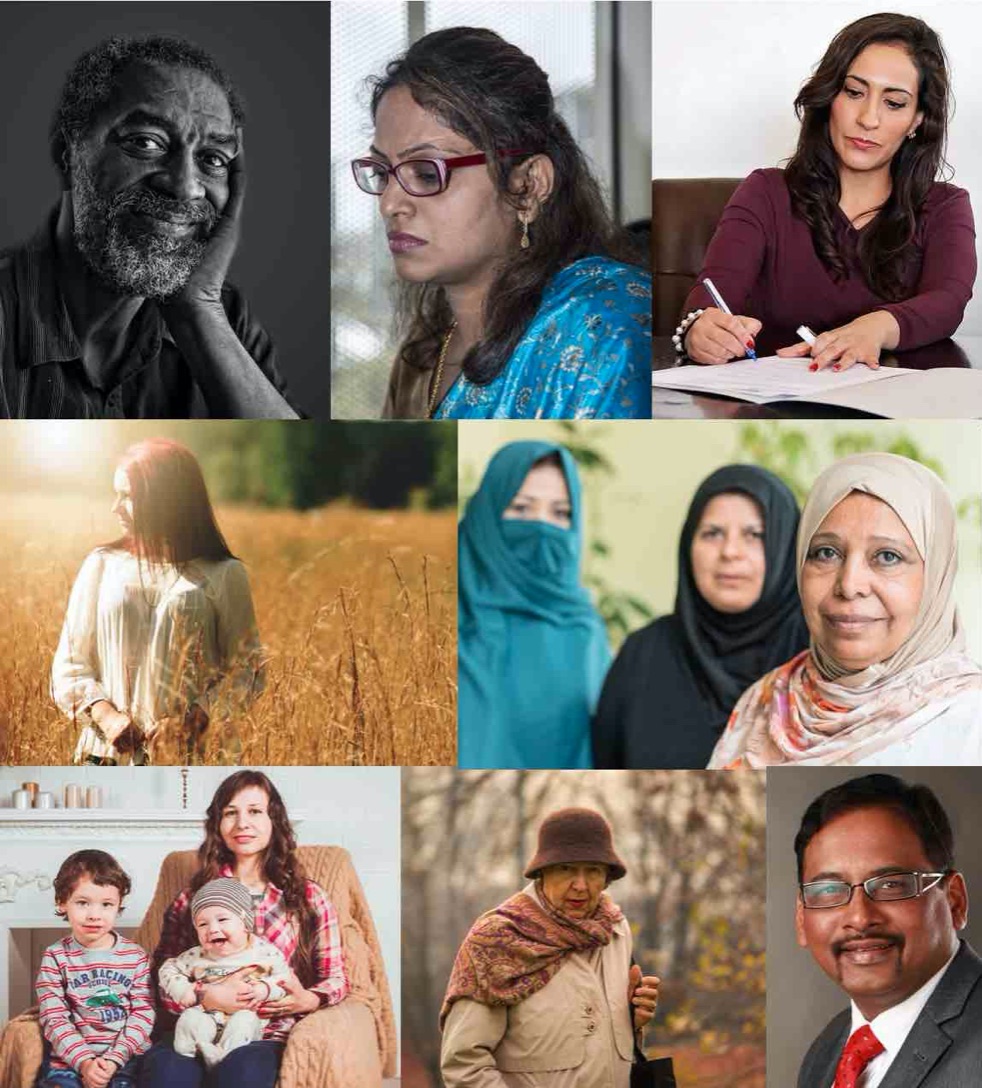

What do you do with the research? Alan Cooper's 'Personas' are a powerful next step - and this is where writing fiction comes in. Based on research, you write descriptions of lots of fictional characters (personas), each representing groups of people with similar goals. They have names, photos and realistic lives. You also write scenarios about their lives that help understand their goals. Next, you merge and narrow these personas down, dropping some, creating new ones, altering others. Your aim is to eventually end up with just one, called a primary persona. The idea is that if you design for the primary persona, you will create something that meets the goals of the groups represented by the other personas it replaced.

The primary persona (let's call her Samira) is then used throughout the design process as the person being designed for. If wondering whether some new feature or way of doing things is a good idea, the designers would ask themselves, "Would Samira actually want this? Would she be able to use it?" If they can think of her as a real person, it is much easier to make decisions than if thinking of some non-existent abstract "user" who becomes whatever each team member wants them to be. It helps stop 'feature bloat' where designers add in every great idea for a new feature they have but end up with a product so complex no one can, or wants to, use it.

As part of the Queen Mary PAMBAYESIAN project we have been talking to rheumatoid arthritis patients and their doctors to understand their needs and goals. I've then created a cast of detailed personas to represent the results. These can act as an initial set of personas to help future designers designing apps to support those with the disease.

If you thought creative writing wasn't important to a computer scientist, think again. A good persona needs to be as powerfully written and as believable as a character in a good novel. So, you should practice writing fiction as well as writing programs.

Find out more about goal-directed design and personas from its creator in Alan Cooper's wonderful book The inmates are running the Asylum (the inmates are computer scientists!)